A letter to Mary Oliver

MY MIND IS A FOREST: An Autistic Wandering through the Poems of Mary Oliver, Pt. I

This is part one of “My Mind is a Forest.” Read part two here.

She can’t see herself apart from the rest of the world or the world from what she must do every spring. Crawling up the high hill, luminous under the sand that has packed against her skin, she doesn’t dream, she knows she is a part of the pond she lives in, the tall trees are her children, the birds that swim above her are tied to her by an unbreakable string. —From Mary Oliver, “The Turtle," Dream Work

CONTENTS || Introduction | Epigraph | “Dear Mary”

INTRODUCTION

I spent most of last year researching and writing about Autistic Poetics, or the poetry of autistic experience and embodiment. Finally, after hundreds of hours of reading and composing, I get to share this work with you.

I couldn’t draw the line between where my autistic experience ends and my poetic imagination begins. For me, in this body, they are one and the same. As I researched this overlap, I found poetry as a kind of shared language between autistics and nonautistics—it invites us into a world that is sharply focused on a moment, on the senses, on the language of silence, and it somehow puts it all into words.

Below is part one of four of “MY MIND IS A FOREST: An Autistic Wandering Through the Language of Silence and the Poems of Mary Oliver.” Mary’s work, which is beloved by so many of us, works as a common ground in its familiarity, accessibility, and practicality. We know it. We see ourselves in it, whatever that might mean to each of us—whether we are simply fans of “Wild Geese” or we (as I do) have teetering stacks of her books on tables and shelves throughout the house. Across neurotypes, we find something in Mary’s work to treasure, to reflect upon, to hold dear.

This first essay is an introduction to the ones that follow: an explanation of sorts to the poet who invites us to see ourselves in her words. Parts two through four are autistic reflections on poems from her book Dream Work. I’ll be sharing those in weeks to come.

As I wrote in the essay that contextualized this work for my academic setting: I want, through this series of essays, to offer something almost synesthetic to you, Dear Reader—something you may read with your eyes or perhaps hear with your ears, that you might also taste or touch somehow. Something sensory, haptic, humming. Something by which you understand not what autism looks like from the outside, but what, to me, it feels like from within.

There is a good deal of irony involved in trying to define a poetic that is distinguished by its kinship with the inexpressible. Autistic Poetics is a way of communing with the more-than- human world; it is not defined by categorizing, describing, naming, but by simply being with. How am I to translate a poetic like this into something classifiable, describable, without stripping it of all its meaning? There is a reason I come to this work as an artist. Nevertheless, I have a duty here to explain.

I wrote to my friend

, a fellow poet and artist-scholar, with this conundrum. I asked her, how do we define poetics? How do we describe poetics without, in the process, stripping them of their very essence? She answered, as an artist does, with poetry—with what the poetic is like. She described a photograph that hangs on her wall. It is of her maternal grandmother standing at the gas stove, looking over her right shoulder toward the camera that is snapping her picture. She continued,That is poetry. To feed your children, to make something of a life under so many constraints that can’t be seen in a photograph. To laugh, to eat well, to nourish, to touch the ground and grow something. To feed birds as people are being bombed. To live your life in these ways that have a lyricalness and a musicality... the lesson is what it is, the picture is what it is, the life is what it is, but it is so much more than that... Fleshy and human and true.

“Poetics,” she summarized, “speaks to the creative capacity, the metaphoric, the turn of phrase, the way that people are living their lives, and the ways that their knowing, being, doing can reflect and elucidate a kind of poetry.”

So an autistic poetic is, I suppose, what it is like to know the world autistically—to feel the energy in every shuddering atom. To know everything as living, from the table to the maple, the bear and the sky and the mother. To intuitively decategorize; to exist as both a singular sensing body and part of everything. When I speak of Autistic Poetics, then, I am not only talking about autistic poetry, but autisticness as a poetic way of relating.

I am not here to describe autism, but to incarnate the poetry of autistically being: being in the world, with the world, among the world.

The medical model of disability largely presents a culturally-constructed, outside- looking-in understanding of autism; one which suggests autism is a state of brokenness in need of fixing. We are isolated, we are inherently unrelatable. I vehemently reject this narrative. It is so uncurious. So unpoetic.

I reject, too, the diminishment of autistic people to what can be observed by a notetaking onlooker. I am not merely an incarnation of diagnostic criteria. Yes, I stand in my kitchen and flap my hands between steps in a recipe, and when I forget what I’m looking for at the grocery store, and when a boy band triggers my nostalgic joy at a music festival. Yes, I hold my head in my hands and clench my jaw through the droning on of white noise. My eyes enjoy straight lines and will seek them in the space around you while you talk. I listen better this way. Yes, I laugh when I am mad and I know all about mustelids and I cannot take a hint. This is all true.

And I am not here to tell you about it, how I contrast to a normative way of being. Which boxes I checked to secure a diagnosis. I am not here to let my body be reduced to what has been storied as involuntarity, to borrow from M. Remi Yergeau, who laments that “autism’s essence, if you will, has been clinically identified as a disorder that prevents individuals from exercising free will and precludes them from accessing self-knowledge and knowledge of human others.” I am here to subvert this story, too often told, too often believed.

I am here to talk about Autistic Poetics—the entanglement of the autistic and the poetic in a single bodymind. About the silent, inviting breadth of poetic margins; what that silence might have to say about the autist’s place in the world. Also the poet’s. I am not here to describe autism, but to incarnate the poetry of autistically being: being in the world, with the world, among the world. Here, the leaves fluttering in the wind are not a metaphor for my hands at a concert. Here, the leaves fluttering in the wind are leaves fluttering in the wind, and I am here to listen, autistically. I am here to bear witness to their many quiet voices, and to the tree whose body they sustain. To the roots and the earth, to water and light. To the silence we treasure and the will to live we share.

MY MIND IS A FOREST: An Autistic Wandering Through the Poems of Mary Oliver | PART ONE

Mark McCloskey wrote:

Mary Oliver is among the more philosophical pastoral poets currently writing in the United States. She is not content merely to express her psychological difficulties in pastoral settings; she treats nature, in giving her life, as a source of ontological truth, and she tries to give it more than personal meaning. In this sense… she is a Romantic, and as such, she adopts a childlike stance as she faces nature. She wants to appear open, cleansed, simple, and in so doing, she often seems somewhat silly and cute. She has no sense of humor, it seems, and thus her poetry lacks a certain common sense. Carefully elegant as her style is, her personifications of nature, for example, amount to pathetic fallacies. If she were a real child, for whom everything is new, including language, her perceptions might be somewhat fresher than they indeed are.[ii]

DEAR MARY

I would like to ask you about the world, the poetic world, the poetry of earth and bird and gold sun strained through flickering foliage. Wind-licked leaflight. The reflection of a star dancing stop-motion on the laughing face of the water. I would like to ask you about the poetry too of your body, of mine, how people like us—I think I can rightly say “like us”—sit on a bayside stone and, despite our flesh and bone, become it.

I sit on a bayside stone and feel my body enter the earth, enter the earthwater, enter the roots of trees who drink their light and breathe out air, and suddenly I am sky, I am floating. Up here, above, I can see sun particles, little flecks of golden day glittering. I reach out to touch them and my hand is nothing but glittering day, golden sun-sky-air, breath in the mouth of leaves, leaves on the rainbellied tree; tree stood in the mud of the ground that is also me; me somehow a person still sat on a stone by the bay. When I stand to leave, it is with the effort of uprooting. Mary, I would like to know: is this the imagination you speak of so often?

I hope it’s alright that I call you Mary. In my imagination, at least, we would be friends. The kind who are comfortable walking side-by-side in silence, feeling, acknowledging. The best kind, one might argue. People who seem to sprout up from the earth in quietude, gratitude, faces turned softly to the sun as your sunflowers: “they are shy // but want to be friends…”[iii]

We are the sort who do the hard work of growing into this world, not out of it. “To be a poet,” autistic scholar Anna Nygren wrote, “is to be, to be, to be.”[iv] I can’t speak for you, nor your reasons for orienting yourself to the earth as you do. I will not speculate about your neurotype, fill in the blanks of you with stories about me. You have, through your poems and prose, spoken for yourself. But I am autistic. And this is why I am, like you, at home with soil, acorn, maple, robin, cloud. I am at home with them in ways I have never felt quite home with humanity, though do I care very much for people. I orient myself to the world as I do because I know no other way to be, to be, to be.

Why must it be us who come from elsewhere, from the far reaches of space, when we can close our eyes and hear the earth-trees speaking? If this is our mother language, then this is our mother world.

An autistic friend recently said, in a refrain I hear often in autistic circles, “I would not be surprised to learn I was an alien.” She asked, “Would you?”

I considered the question. I thought back across this lifetime where I have felt almost unendingly adrift and displaced among people. Unsettled, unsure. “Oh, I wanted // to be easy / in the peopled kingdoms, / to take my place there, / but there was none // that I could find / shaped like me.”[v] I thought of the disconnect I feel from humanity, from our hunger for power, our wishes to rule. Then I thought of Mark McCloskey’s review of Dream Work, his disdain for your “pathetic fallacies” and his distrust of your wonder. I thought of screens and jobs and trains. I thought of my roots in the earth, of stillness and slow-growing. And I decided I would be very surprised indeed to discover I am an alien, but I would not be surprised in the least to learn Mark McCloskey is one.

Why is it that autistic people must be the aliens when we are the ones who know we belong to the earth? Why must it be us who come from elsewhere, from the far reaches of space, when we can close our eyes and hear the earth-trees speaking? If this is our mother language, then this is our mother world. I wonder if the neuromajority has ever considered that it is even possible it is they who came from elsewhere, they who don’t belong.[vi]

Each sunflower, you wrote, “is lonely, the long work / of turning their lives / into a celebration / is not easy.”[vii] Perhaps this is true of all of us who seem to spring up from the ground. As I ponder what it means to be different in this world—to be alienated, pathologized, misunderstood, and Mark McCloskey’d—I maintain this Turning is a work of resistance. It is work that must be done.

Suddenly the clothes I wore to impress felt ridiculous on me, hanging from my limbs like cheap tinsel on a five-hundred-year-old conifer with nests in her hair.

In some ways, Mary, I think your poetry was the beginning of my knowing that. At the very start of my work as a poet, I was living in Los Angeles and writing poems for clients on commission. One wrote me saying, “I want a poem in the vein of Mary Oliver’s ‘The Journey,’” and that is where I met you. “One day you finally knew / what you had to do, and began, / though the voices around you / kept shouting / their bad advice…”[viii]

Once I had read you, I read, and read, and read you. You gave me something and many things—a sense of companionship, a language for my perceiving, a new vernacular. Weights in the pockets of my beliefs that brought me from the heavens back to the soft earth, which welcomed me with patience and kindness. Suddenly this godward gaze I’d been raised with felt entirely misdirected—my looking up rather than at the lemon tree in the side yard, the cool earthworm in the palm of my warm hands. Suddenly the clothes I wore to impress felt ridiculous on me, hanging from my limbs like cheap tinsel on a five-hundred-year-old conifer with nests in her hair. I began to let myself change, or rather, to throw off the changes that had been put on me. I, like you, fell in love with a woman. The backlash to my saying so was swift and blunt.

But little by little,

as you left their voices behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice,

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do —

determined to save

the only life you could save.[ix]

In the spring after I turned thirty-two, I discovered I’m autistic. As I had before, I turned to poetry. When I returned to school, I began to explore Autistic Poetics—this poetry of autistically being—and once again found your poems as a kind of scripture. I don’t mean this to imply that you are autistic too. There is so much about you I don’t know, questions I have that you aren’t here to answer. But whatever the reason, the way I feel at home on that stone at the bayside, where the tides carefully keep their easy rhythm, this is how I feel at home in your poems. I don’t skim their surface, I am submerged. Letters above and below and around me, a sea swimming with words and pictures and sunflowers and foxes. I am in their waters, the world. I am connected from every side. Being in your poetry is, for me, a way of being alive. A way to be, to be, to be.

“For years and years I struggled / just to love my life. And then // the butterfly / rose, weightless, in the wind…”

I am here now to share this being. This poetic autisticness that somehow, in its merging with the earth and her more-than-human children, brings incredible joy and contentment—even while living among people who seem determined to keep us unhappy.

Mark McCloskey says this merging (which you and I share) is childish, is humorless, is tired. He says it’s silly and cute. It lacks common sense.[viii] Mark McCloskey strikes me as proud and disconnected. He seems to mandate this posture for the rest of us. I dissent. “For years and years I struggled / just to love my life. And then // the butterfly / rose, weightless, in the wind. / ‘Don’t love your life / too much,’ it said, // and vanished into the world.”[xi] And vanished into the world. What is so wrong with that?

Despite Mark McCloskey and critics like him, your poems are precious to the masses. You are beloved by so many readers who have found solace in your words through times of crisis, grief, loss, and new life. You have called attention to the beauty of the world, to the absurdity of our apathy in our exploitation of it.

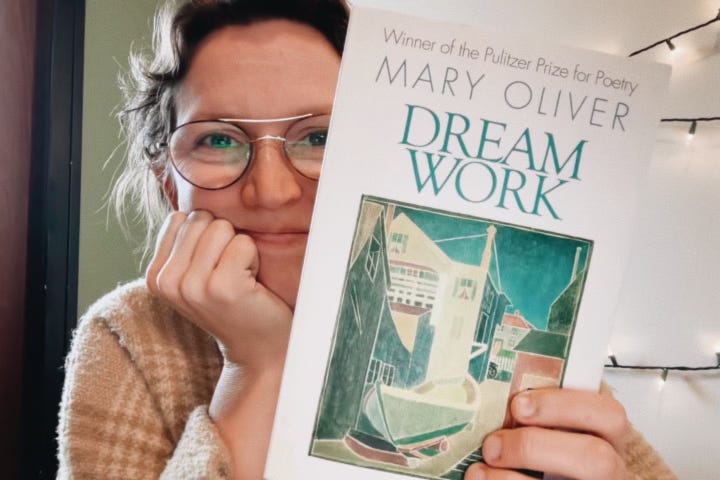

I sit now with a copy of Dream Work in my lap. It feels amazing in my hands, these soft, ready pages full of wisdom and silence. In the essays to come, I’ll be using these pages to explore Autistic Poetics. I’ll be engaging them as an autistic reader. I’ll also be playing with the possibility of these poems, regardless of your neurotype, being read as autistic poems.

I trust this is okay with you. In the rare interview you gave Krista Tippett, you said, “I wanted the ‘I’ [in my poems] to be the possible reader rather than about myself. It was about an experience that happened to be mine but could well have been about anybody else’s.”[xii] In, perhaps, true autistic fashion, I take this literally. I am so grateful to get to engage your poetry as though the speaker—the one sensing, interpreting, relating—could be me.

I hope, through engaging these poems with fluidity—through fusing with the speaker and her world—I will be able to evidence the vitality of Autistic Poetics, the poetry of neurodivergence, and the beauty and urgency of an autistic ecological ethic. I will articulate all this in a common tongue: the familiar language of your poems, the poems of Mary Oliver. I come to your work now with reverence, wildness, and thankful attention. I hope I do you justice.

Thank you, Mary. May your memory be a blessing.

ENDNOTES

[i] Martin Silvertant, “Thinking Styles in Autistic People,” Embrace Autism, May 24, 2023, https://embrace-autism.com/thinking-styles-in-autistic-people/#Bottom-up_analytical_lateral_and_associative_thinkers.

[ii] Mark McCloskey, “Dream Work,” Magill’s Literary Annual (1987): 3.

[iii] Mary Oliver, “The Sunflowers,” in Dream Work (New York: First Grove Atlantic, 1986), 88-89, lines 12-13.

[iv] Nygren, “Empathy with Nature,” 107.

[v] Mary Oliver, “Trilliums,” in Dream Work (New York: First Grove Atlantic, 1986), 10, lines 8-14.

[vi] If this rankles the neurotypical reader who happens upon this letter, I’d urge them to consider this: that autistic people across the spectrum are othered for our orientation to the world around us all the time. One could argue this (dis)orientation is central to the cultural understanding of autism, which is measured and described in terms of perceived deficits in empathy, social idiosyncrasies, and a general out-of-placeness among people. If it unsettles the neurotypical onlooker—this suggestion that perhaps it is their natural way of relating to the world that ought to be scrutinized—perhaps this should be the beginning of a deeper empathy for autistic people.

[vii] Oliver, “The Sunflowers,” 89, lines 29-32.

[viii] Mary Oliver, “The Journey,” in Dream Work (New York: First Grove Atlantic, 1986), 38, lines 1-5.

[ix] Oliver, “The Journey,” 38-39, lines 23-36.

[x] I have yet to meet an autistic person who has not been called at least some of these things.

[xi] Mary Oliver, “One or Two Things,” in Dream Work (New York: First Grove Atlantic, 1986), 88-89, part 7.

[xii] Krista Tippett, “Mary Oliver: ‘I Got Saved By the Beauty of the World’,” February 5, 2018, in On Being with Krista Tippett, podcast, 93:13, https://onbeing.org/programs/mary-oliver-i-got-saved-by-the-beauty-of-the-world.

this is absolutely stunning! So many lines (images, sensations) swirling in my mind and humming in my heart; thank you for sharing here! You are offering an incredible contribution…just incredible. 💞

This post was the first thing I read this morning. I can’t even explain how beautiful and meaningful it is to me. Lately, I’ve been feeling myself being pulled away from the digital world. I’ve been carefully considering what’s worth keeping, worth the energy. I keep coming back to Substack for voices like yours. I might stay a while, looking for other sunflowers.🌻